Chapter 6: Approaches to spoken discourse

Essential reading

Cameron, D. Working with Spoken Discourse. (London: Sage, 2001)

[ISBN 0761957731].

Holmes, J. An introduction to Sociolinguistics. (Harlow: Pearson Education, 2008) third edition [ISBN 9781405821315] Chapter 14: ‘Analysing discourse’.

Further reading

Coupland, N. and A. Jaworski Sociolinguistics: A Reader and Coursebook. (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 1997) [ISBN 0333693442] pp.341–52.

Gee, J.P. and M. Handford (eds) The Routledge Handbook of Discourse Analysis. (Abingdon: Routledge, 2011) [ISBN 9780415551076].

Gumperz, J. ‘Interethnic communication’ in Coupland, N. and A. Jaworski (eds) Sociolinguistics: A Reader and Coursebook. (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 1997) [ISBN 0761957731] pp.395–407.

Ten, Have, P. Doing Conversation Analysis: A Practical Guide. (London: Sage, 2007) second edition [ISBN 9781412921749]

Hutchby, I. and R. Wooffitt Conversation Analysis.(Cambridge: Polity Press, 2008) second edition [ISBN 9780745638669].

Hymes D. ‘On communicative competence’ in Pride, J.B. and J. Holmes Sociolinguistics. (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1972)

[ISBN 9780140806656] pp.269–93.

Sacks H., E.A. Schegloff and G. Jefferson ‘A simplest systematics for the organization of turn-taking for conversation’, Language, 50 1974, pp.696–735.

Other works cited

Eggins, S. and D. Slade Analysing Casual Conversation. (London: Cassell, 1997) [ISBN 0304337285].

Fairclough, N. Language and Power. (London: Longman, 2001) second edition [ISBN 9780582414839].

Labov, W. Sociolinguistic Patterns. (Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1972) [ISBN 9780812210522].

McDonald, C. English Language Project Work. (Houndmills: Macmillan Press, 1996) [ISBN 0333541170].

Pichler, P. Talking Young Femininities. (London: Palgrave, 2009)

[ISBN 9780230013285].

Pichler, P. and S. Preece Chapter 5 ‘Language and gender’ in Mooney et al. Language, Society and Power: An Introduction. (New York: Routledge, 2010) [ISBN 9780415576598].

Introduction

In this chapter we outline some approaches sociolinguists use when analysing spoken discourse. There are several approaches, but we will consider three of the most well known: Conversation Analysis, the Ethnography of Speaking (sometimes referred to as the Ethnography of Communication) and Interactional Sociolinguistics. Each of these approaches may be used by analysts as their sole approach, but they may also be used in combination, depending on the source material and the background of the analyst. This will become clearer as you work through the chapter and start to make your own study of work that has been done.

In addition to outlining theoretical and methodological approaches to the analysis of spoken discourse, we will reproduce some transcriptions of spoken conversation so that you can become familiar with the way they are represented. We will start, however, by considering what we mean by ‘discourse’, a term which can be applied to either spoken or written texts.

The term ‘discourse’

The term ‘discourse’ is not straightforward or easy to define. It is what is known as a contested term within the social sciences, which means that it has different meanings attached to it because it is used in different ways and within several academic disciplines. Linguists use the term to refer to language, spoken or written, which extends beyond a sentence or utterance. Some researchers, however, particularly those from other academic disciplines, use the term ‘discourse’ to refer to the way in which knowledge and social relations are structured in any given society. The French philosopher, Michel Foucault, has been very influential in this conception of discourse. Some sociolinguists, for example, Norman Fairclough (2001) have been heavily influenced by Foucault’s work. Fairclough has developed an approach known as Critical Discourse Analysis which is dealt with more fully on another module, Language and the Media, and also referred to briefly in Chapter 8 of this guide. In this chapter, however, we concentrate on the three approaches we have referred to in the introduction.

Activity

Read Cameron (2001) Chapter 4 and carry out some further research into the term ‘discourse’, in books or on the internet. Summarise the similarities and differences in the meanings of the term that you come across.

Now we outline three ways of analysing spoken discourse. There are others (such as pragmatics) which are also outlined in Cameron (2001), but we will not deal with them here. First, we look at an approach called Conversation Analysis, which was developed by sociologists and now used by sociolinguists and social psychologists. It is what is known as a micro or bottom up approach because it involves analysing in great detail everything that occurs within a stretch of talk. In addition, the analyst will focus on how we manage conversations using a number of strategies that we may not be consciously aware of, even though we automatically follow the rules that those strategies involve.

Conversation Analysis

Harvey Sacks was a sociologist who, through his work in Los Angeles in the 1960s, gained access to tape recordings made to a telephone suicide helpline, which were then analysed. In a seminal paper, Sacks and his fellow researchers, Emmanuel Schegloff and Gail Jefferson (1974), proposed the following:

- • In conversations speakers take turns.

- • There are rules that speakers follow which determine how those turns are organised and how speakers select who speaks.

- • Usually only one person speaks at a time.

- • If more than one person speaks at the same time, this does not last for very long.

- • The transition from one person speaking to another person speaking is very often made seamlessly.

- • Turn taking is not fixed beforehand so there must be some way of allocating and distributing turns.

- • Conversation is locally managed by those involved who make their contributions relevant for their interlocutors. This is known as recipient design. As Sacks et al. put it:

By ‘recipient design’ we refer to the multitude of respects in which the talk by a party in a conversation is constructed or designed in ways which display an orientation and sensitivity to the particular other(s) who are the co-participants.

(Sacks et al., 1974, p.727)

The rules that speakers unconsciously adhere to in the way they structure their talk and select who can talk at any given time can be outlined as follows:

Speakers know where it is possible for speaker change to occur because participants in a conversation speak in turn construction units or TCUs. Speakers know that a turn consists of one or more TCUs and we can recognise the end of a TCU. This marks what we call a Turn Transition Relevance Place or a TRP and it is at this point that a change of speaker can occur.

In addition to grammatical cues that speakers recognise, there are also non-linguistic signals which tell participants where a change can occur; for example, gaze, posture, gestures and so on. Cameron (2001, p.90) gives the example of someone saying ‘and that’s what I did today’ with falling intonation and a pause which shows it’s likely to be interpreted as a TRP. On the other hand saying something like ‘And do you know what she said to me?’ would show by the rising intonation pattern and interrogative structure that that was not the end of the turn and the speaker will be allowed to continue to hold the floor until they have finished telling whatever it was that ‘she said to me’.

When a TRP is reached and speaker change occurs, either:

- • the current speaker selects the next speaker (this may be explicit; for example, ‘So what happened then Gina?’)

or

- • the next speaker selects themselves

or

- • the current speaker continues.

As we have noted, more than one person could self-select (that is, more than one person could begin speaking at the same time) but if that situation arises it is usually the case that someone gives way quite quickly and only one speaker continues to hold the floor.

In addition, Sacks et al. observed that conversations are structured according to certain sequences. An extremely important and common sequence is known as the adjacency pair structure. This describes two utterances by two speakers which are related and adjacent to one another. What is known as the second pair part (that is, the second utterance) is related to and dependent on the first pair part. Some common adjacency pair structures are Question/Answer; Greeting/Greeting and Offer/Acceptance or Refusal.

Here are some examples of types of adjacency pairs and their first pair parts with possible second pair parts.

| An offer: | acceptance | refusal |

| Question: | relevant answer | irrelevant or non-answer |

| Greeting: | greeting | no response |

Activity

The most frequent type of adjacency pair structure used in conversation is Question/Answer. Why do you think this might be?

For some adjacency pairs there could be more than one relevant or related response that could be made. However, one second pair part may constitute what is called ‘the preferred response’, while the other may be the ‘dispreferred response’ (see Cameron 2001, p.97, for a critical discussion of these terms, and Hutchby and Wooffitt, 2008, for further reading).

Activity

If someone asks another person to do something, that person may agree and accept or disagree and refuse to do what has been asked. Which is the preferred response and which is the ‘dispreferred’ response?

The dispreferred response, for example, a refusal of an invitation, is often elaborated on, so if someone asks another person out for dinner and that person is unable to go or doesn’t want to go, they may refuse (or decline) but rather than simply say, ‘No thanks’, there will probably be an explanation as to why the invitation is being refused (for example, ‘No thanks, I can’t come because I’ve got to visit my mother this evening’).

Sometimes it isn’t that easy to pick out adjacency pairs because they have insertion sequences within them as in the following example:

A: May I have a glass of red wine please? Q1

B: How old are you? Q2

A: Eighteen. A2

B: No, sorry, I'm afraid you have to be 21 to drink here. A1

Activity

In addition to the fact that the answer to Q1 comes after an insertion sequence, what else is apparent about the A1 response?

Additional points about Conversation Analysis

Conversation Analysis as theory and method can be used to analyse any type of talk from casual talk, transactional encounters through to institutional discourse (the type of conversations that may take place in societal institutions, for example, in a courtroom, in politics or in the workplace).

Scholars who practise what is known as a ‘pure’ CA approach in their analysis of talk disregard anything outside of the talk itself. This means they do not consider contextual factors such as gender, age, class and so on unless the participants within the stretch of talk that is being analysed highlight the relevance of such factors explicitly. For CA scholars, the analysis derives only from the talk itself. Other researchers argue that a ‘pure’ approach is short-sighted and it is impossible to ignore contextual factors. This does not mean that researchers who take the latter stance will ignore CA completely as a method. On the contrary, often the ‘tools’ from CA about the turn-taking mechanism will be used alongside other frameworks (some of which we will discuss shortly). The work that Sacks et al. have carried out is important and ground-breaking in our understanding of the structure of talk including the way in which participants organise themselves in conversations, no matter which approach we are using to analyse conversations. As Eggins and Slade (1997, p.31) put it, ‘The debts owed to early CA by all subsequent approaches to Conversation Analysis (and to discourse analysis more generally) cannot be overstated’.

Activity

Watch some talk show programmes, celebrity or politician interviews on television (or listen on the radio). Focus on how the question and answer adjacency pair structures the conversations. Consider the concept of conditional relevance and also the part that recipient design plays.

Activity

Read the section in Cameron (2001, pp.98–100) on telephone conversations. Next time you are on the telephone, or you hear someone on the telephone, think about the way openings and closings are managed.

We turn now to consider two other approaches to analysing talk. It is possible to combine these approaches with the tools from CA in an analysis.

The Ethnography of Speaking

The Ethnography of Speaking is an approach which was developed by Dell Hymes in the 1970s. Hymes is sometimes viewed as the founder of sociolinguistics. He was an anthropologist. Anthropology and linguistics were, however, at that time, seen as quite separate disciplines. Until the 1970s Chomsky had been the dominant figure in linguistics but Hymes and other scholars reacted against what they saw as the idealised way that language was studied at this time. Chomsky had made a distinction between competence and performance. While competence refers to what people (subconsciously) know about their language and how to use it, performance refers to how they do actually use it.

Hymes was interested in what he termed as communicative competence (Hymes, 1972). Not only do speakers have knowledge of how their native language works, but they also have knowledge of the social and cultural rules of a language. As speakers we generally produce the ‘right’ utterances at the ‘right’ time. If we don’t it’s noticed and seems odd. Producing the right talk at the right time involves sociocultural knowledge. In order to research how people use their sociocultural knowledge when speaking, Hymes developed what became known as the Speaking Grid. This is an aid to analysis for the ethnographic researcher who may be analysing talk in cultures other than their own (although ethnographers do also research their own cultural practices). The Speaking Grid is used to analyse speech events which can only take place through the use of talk. A speech event will take place within a speech situation (speech situations provide a context for communication or talk). Cameron (2001, p.55) illustrates this with the example of a speech situation such as a family dinner. Arguments and discussions are two types of speech event that might occur during a family dinner, but other things may happen which do not involve talk (kicking people under the table, for example).

Hymes listed a number of components of speech events, which provide a descriptive framework for the Ethnography of Speaking (or Communication). This is an eight part mnemonic based on the word SPEAKING: the Speaking Grid. These components help ethnographers to analyse and understand the speech event and the language choices made by speakers in the speech event. You should note that there is no theoretical significance as to why the word SPEAKING is used: it is simply an aid to remembering. Here are the components and the description of what to apply them to in an analysis:

Situation: setting (physical; temporal) and scene (psychological – cultural definition of occasion as formal or informal, serious or festive etc.)

Participants: who takes part in the speech event and in what role: speaker and addressee but also addressor (originator, source) and audience (who can evaluate)

End: goal/purpose of exchange, e.g. compliment (expression involving positive politeness)

Act sequence: message form (how things are said; which speech acts and in which order) and content (what is said; topic); and the relationship between the two

Key: manner or spirit in which it is carried out, e.g. mocking or serious

Instrumentalities: which channel is used (writing, speaking, etc.) and which language variety is selected from speaker’s repertoire

Norms: of producing and interpreting interaction/speech acts (this involves ‘reading between the lines’)

Genres: what ‘type’ (poems, proverbs, sermons, lectures, conversation) does a speech event belong to and draw on?

You should be aware of the fact that it is not always easy to fit the data you may be analysing into the framework, but rather than ‘forcing it‘ it might be more productive to consider why it does not fit (Cameron, 2001, p.57). A further point is that it is often the case that students using this framework for the first time will describe the data, fitting it into the categories without explaining what this shows or indicates about the speakers and their use of language. In all your work, you should ensure you analyse rather than simply describe.

Activity

Read the analysis of the Pentecostal meeting in South London in Cameron (2001, pp.58–65) and the Kros in Papua New Guinea. Then consider an event you are familiar with and analyse it using the categories provided by the Grid.

Activity

The Ethnography of Speaking seems to provide a useful framework for analysing speech events in cultures other than one’s own. Can you think of some reasons why it might also be a useful aid to an analysis of speech events within the researcher’s own culture?

Interactional Sociolinguistics

The last approach we will consider in this chapter was developed by John Gumperz, who, like Dell Hymes, was one of the founders of the discipline of sociolinguistics. In fact, Gumperz’s approach developed out of the Ethnography of Speaking framework, but Gumperz was also concerned with the way in which people interpret conversation, which he believed (and, in fact, demonstrated) was culturally specific.

Interactional Sociolinguistics shares some of the interests with CA with respect to turn–taking mechanisms. However, while the ‘pure’ CA analyst will disregard context, the Interactional Sociolinguist will regard the sociocultural context in which a conversation takes place as an essential component in an analysis. Indeed, the cultural background of participants in a conversation will determine how they make inferences and interpret what Gumperz called contexualization cues. Contextualisation cues refer to the ways in which we signal to listeners how they should interpret our words and utterances. These cues may take a number of forms: they may consist of laughter, teasing, rising or falling intonation. They may consist of facial expressions, sighs, gestures and even silence. Contextualization cues therefore provide crucial information in our understanding of what is being said to us.

As Cameron (2001, p.107) points out, the interesting aspects of conversation that interactional sociolinguists focus on are often those things of which speakers are unaware such as their minimal responses (for example: mhm, yeah, right). In some contexts, these can signal attentive listening; in other situations, the manner in which they are uttered can indicate dismissiveness. Discourse markers (for example: oh, well, okay now, you know) are other features which are often regarded as carrying little meaning in conversation, being variously described as meaningless or fillers. The interactional sociolinguist would argue, however, that even these small elements are there for a reason and ‘mean something’ in people’s talk.

Problems can arise, however, in situations where speakers do not share the same cultural background, as they may interpret the contextualisation cues differently, causing misunderstandings. A major strand of Gumperz’s work involved interethnic communication or miscommunication. Gumperz demonstrated the potential for misunderstanding in interethnic or cross-cultural communication, how this could lead to bad feelings and sometimes serious disadvantage in certain situations.

An example Gumperz (1997) gives involves catering staff in a staff canteen at Heathrow Airport, London. The Asians who served in the canteen were perceived to be surly and rude in the way they served the British cargo handlers who were offered ‘gravy’. The problem was that ‘gravy’ was uttered with falling intonation rather than rising intonation, the latter being the usual way in which ‘gravy’ would be offered to customers in this situation. Uttering the word ‘gravy’ with falling intonation was misinterpreted as meaning that ‘This is gravy’ so it did not seem to be an offer to the cargo handlers but a statement which, in this context, appeared rude. For the Asian workers, however, using falling intonation in this situation was the normal way of asking questions (Gumperz, 1997, p.396). When it became apparent that misunderstandings had arisen, it was possible to bring people together in sessions so that all parties could understand that no bad feeling was intended on either side.

Interactional Sociolinguistics is therefore concerned with the knowledge that we bring to bear in our interpretations of what someone is saying to us and the knowledge we assume others that we are talking to share with us. The example outlined above highlights that problems which can have quite serious consequences can arise if these small details mean different things in different cultures. Misinterpretation can lead to uncomfortable feelings, financial disadvantage or even job losses: these are all matters that John Gumperz makes us aware of in his work.

Activity

Study the research summarised by Cameron (2001, pp.112–21) on the case of ‘uptalk’ and on minimal responses. What observations can you make about the way the talk was analysed? What is different about the analysis compared to a possible analysis made using a CA approach?

Representing speech in writing

Despite their differences, practitioners using Conversation Analysis, The Ethnography of Speaking or Interactional Sociolinguistics are all interested in finding out more about how speakers actually use language in real life situations. If you are going to analyse spoken language of any kind, however, it needs to be recorded and written down. The process of writing down natural, spoken language is frequently referred to as ‘transcription’ by sociolinguists. As Cameron (2001, p.31) observes, no matter how much you wind and rewind, or go back over a recording you have made, you cannot really begin to analyse it unless you have made a written transcript. To begin with, it would be highly unlikely that you would remember a whole two minutes of conversation that you had heard, even if you have heard it many, many times. If you produce a written version of the talk you have recorded, it will then be possible to move towards an analysis of it, using the frameworks we have outlined above. This section concentrates on how you might approach this task.

There are different ways to transcribe and researchers will have to make important choices according to the data they are transcribing and what they will be focusing on in an analysis. You can familiarise yourself with the different ways analysts represent speech by looking at transcripts and their analysis in sociolinguistic textbooks. There is only one real way, however, to learn how to make a transcription: you have to record some talk and transcribe it! Here are some guidelines to get you started:

Transcription techniques

- • do not use capital letters at beginning of utterances (but do use capitals for proper nouns; ‘I’; etc.)

- • do not use any punctuation like commas, full stops, question marks, etc. unless they are used to signal pauses or intonational patterns

- • you can use apostrophes for contractions, e.g. ‘can’t’

- • use conventional spelling as far as possible, unless other forms have been established e.g. ‘wanna’, ‘dunno’

- • you should mark pauses and differentiate between:

- • micropauses (under a second): (.) or (–)

- • long pauses (measured in seconds): (1), (2), (3)

- • pauses accompanied by an intake of breath: .hhh

- • if you can’t understand something on your recording, you must be honest about this; use (..) or similar to enclose any bits that are doubtful

- • layout: your transcription must be easy to follow and must mirror accurately what’s on the tape

- • number the staves or lines (depending on which transcription system you use)

- • you must include a transcription key at the beginning of your transcript, explain what symbols you have used and what they mean

- • you must include non-fluency features, including:

- • non-fluent pausing – occurs in the middle of a structure where no punctuation would occur in writing: ‘it’s (–) your turn’

- • hesitation sounds – sounds which aren’t words like ‘er’, ‘um’

- • record nonverbal information (e.g. laughter); paralinguistic information (volume; voice quality – for example laughing) and prosody (stress, intonation).

This list was in part informed by a section on transcription in McDonald (1992, pp.32–34).

Activity

Consider the guidelines outlined above. Why do you think capital letters, commas, full stops and question marks are often avoided in transcriptions?

More terminology to use in an analysis

Sociolinguistic and discourse analytic transcripts of natural spontaneous language will also record the following features:

- • discourse markers: these are features such as ‘oh’, ‘well’, ‘like’, ‘sort of’, ‘y’know’, ‘I mean’ which are inserted within and in between utterances and function in different ways, for example as hedges (which reduce the force of an utterance), as pause fillers (filling silence to give time to think). With discourse markers, like so many other linguistic features, their function needs to be determined in context, for example, ‘well’ can function as an initiator (to mark the beginning of a turn: well, I don’t know) or as a hedge/marker of a dispreferred response ‘well, I’d love to join you but. . . ’

- • false starts: this describes an utterance which is started one way but is unfinished and then abandoned for another structure: ‘I wanted to (.) I wish I could have…’

- • repetitions: this is self evident: ‘I wanted to (.) I wanted to talk to you. . . ’

- • recycling: this is similar to repetition but involves a hitch in production; the initial sounds are repeated before the speaker manages to get the word out. This is not the same as stammering/stuttering. ‘I w. wanted to talk’

- • self-corrections: a speaker realises that s/he has made some sort of (grammatical) mistake and corrects it: ‘I wants (I mean) I wanted to…’

The previous two sections demonstrate that, unlike drama, film or soap opera scripts of conversations, nothing is edited out in linguistic transcripts of conversations, as every little detail, including repetitions, pauses and discourse markers, can be significant in an analysis.

Lastly in this section, we reproduce below an example of a transcription key. When you practise recording and transcribing a conversation, you can construct a transcription key similar to the following one, perhaps modifying it to include features that are particularly relevant to your transcription.

Activities

In the activities section that follows, we start with an activity which should ensure you are familiar with the three approaches we have discussed. Next, we move on to helping you put your knowledge into practice. You will have to obtain some sort of recording device for these activities. We recommend some method of digital recording equipment which can be downloaded to your computer so that it can be played back for transcribing. You may be able to make use of a mobile phone or an MP3 player for this purpose.

Activity

Summarise and compare the three approaches to analysing spoken discourse outlined in this subject guide. Identify different situations (types of conversation) where you think it would be appropriate to use each of them.

Further activities (based on those found in Cameron, 2001):

- 1. Record around 15 minutes of conversation .

For your initial attempts, don’t record more than three people talking, otherwise it will be extremely difficult to transcribe. You may be one of the speakers although you might like to consider how this may affect what you talk about.

You must not record people without their knowledge, because it is not ethical to do so. The British Association of Applied Linguists (see www.baal.org.uk) provides strict guidelines about this, even for student projects.

Choose your recording context carefully. Recording friends at the pub or in a restaurant, for example, may be problematic due to background noise. On the other hand, friends and family are a good choice because it is often easier to get permission and you can record them at home or somewhere similar. In addition, you may well be able to negotiate permission to ‘record them at some stage over the next two weeks’ without specifying exactly when. This will allow you to make a recording without your informants knowing exactly when, minimising the impact of the Observer’s Paradox. The Observer’s Paradox is a term coined by Labov (1972, p. 209) and refers to the point that researchers are aiming to capture ‘natural’ speech, but there are difficulties involved in this if you are collecting data following ethical guidelines. This is because if people know they are being recorded, they may modify their behaviour and their speech in various ways.

Record on a device that will make it relatively easy to transcribe. Although tape recorders and cassettes will do the job, digitally recording conversation which can be downloaded for transcription to your computer will make your life easier. Your mobile phone may, for example, have a recording device which is suitable for this exercise.

- 2. Transcribe around two minutes of your recording, then think about the following:

- • What did you include apart from the words? Any or all of the features listed in the section entitled Transcription techniques?

- • What was difficult about this activity? Did you find it more time consuming than you expected?

- • What features did you notice particularly in the talk you transcribed?

- • In what ways is your transcript different from representations of speech you have come across in books, play scripts, newspapers etc?

- 3. Analyse your transcript.

This will involve finding a focus for your analysis. You may want to focus on discourse markers. Or perhaps you are interested in seeing whether men interrupt women in conversation (see Chapter 5). It could be that you are interested in studying how those you have recorded use the quotative ‘be like’.

You will not be able to do any substantial analysis on your extract without doing a certain amount of reading. This will involve researching articles and books about the features you are interested in and reading books about spoken discourse analysis more generally.

Learning outcomes

After working through this chapter, and having done a substantial amount of reading on the topic as well as the activities, you should be able to:

- • discuss different definitions of ‘discourse’

- • write about the differences between naturally occurring spoken language and written language

- • discuss the different theoretical and methodological approaches that can be used in an analysis of spoken discourse

- • reflect on a recording, transcription and analysis of naturally occurring spoken language that you have carried out yourself.

Sample examination questions

- 1. What does Conversation Analysis contribute to our understanding of how spontaneous language works?

- 2. What are some of the meanings of ‘discourse’? Compare and contrast the different definitions critically and consider their applications.

- 3. It is correct to claim that spoken language is unstructured?

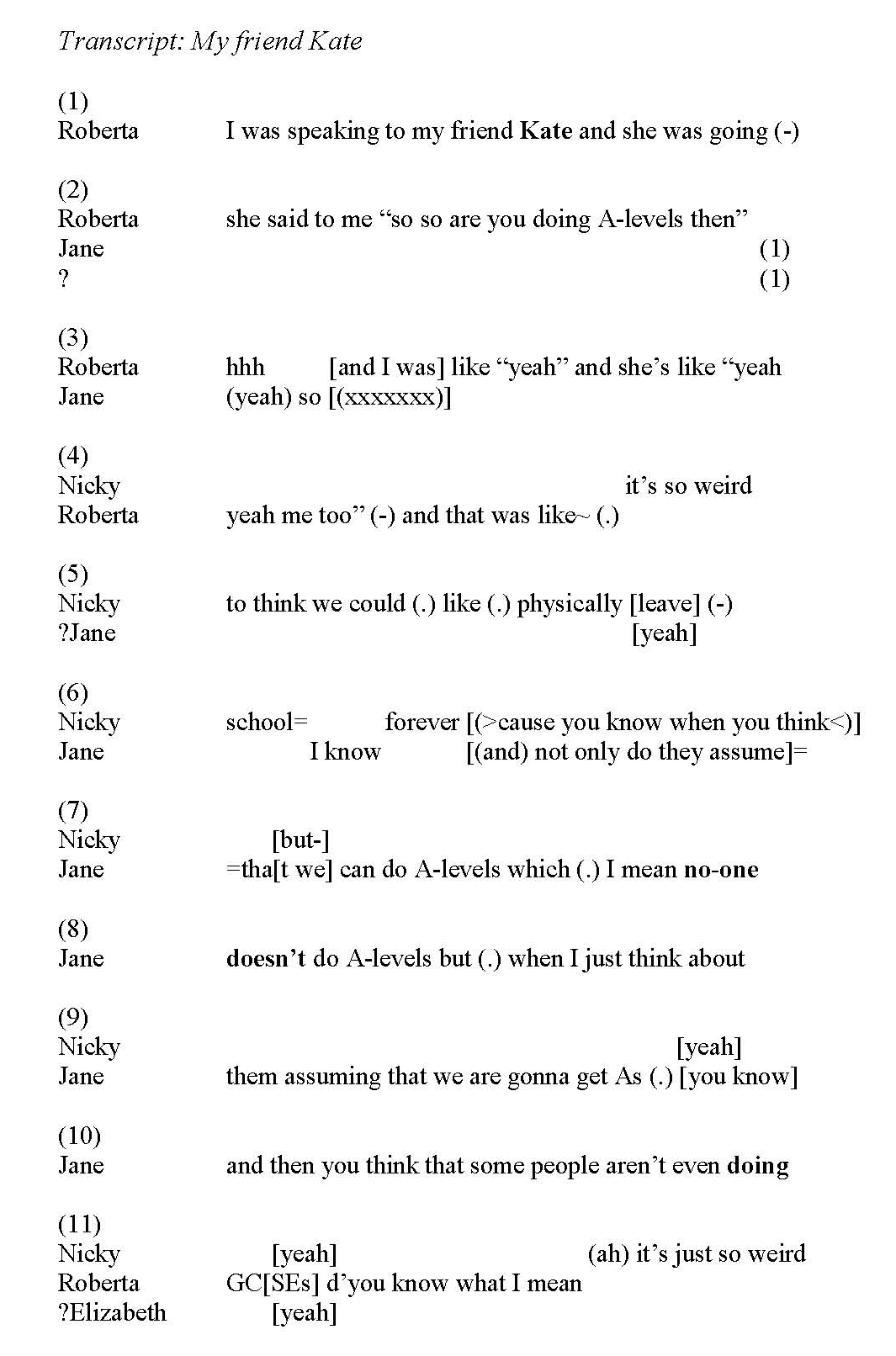

- 4. Study and analyse the following transcript (from Pichler, 2009, pp.51–52), using any method or approach that seems reasonable to you. You may use more than one approach, as long as it is made clear within your analysis that you are doing so and that you are able to apply theories to the data systematically. (Note: in this transcript a '?' in front of the name refers to doubt about the identity of the speaker. (For all other symbols, please see the sample of a transcription key above.)

Transcript: My friend Kate